In the early 19th century the Age of Reason gave way to the age of the imagination and the Romantic Movement.

Young artists, writers, poets and dancers wanted the freedom to express themselves in a spontaneous and individual way. Rejecting the classical ideas of order, harmony and balance they turned to nature as a source of inspiration. As people left the countryside and agriculture for the growing urban industries and factory work, the Romantic vision was partly a plea for a return to a ‘natural’ life and partly escapism.

Although most ballets were created by men, the male dancer was no longer an equal star. In the following decades dance became an unacceptable career for a man. Male roles were often taken by women dressing en travestie. Men only appeared in character roles.

Marie Taglioni, La Sylphide, Alfred Edward Chalon (RA), Richard James Lane (A.R.A). lithograph, coloured by hand, London. Museum no. S.2610-1986

The Cult Of The Ballerina

By the 1840s women had become the great ballet stars and ballerinas wore the familiar bell shaped dress with cap sleeves, low cut bodice and long skirts. If you look at fashion plates of the period you can see that costumes developed from fashionable dress of the time. Ballerinas also learned the art of dancing on the very tips of their toes, known as pointe work. There were no stiffened pointe shoes and dancers darned the toes of their slippers to give additional support.

The great Romantic ballerinas were idolised throughout Europe. Marie Taglioni danced in Paris, St Petersburg, London and Italy and Fanny Elssler even toured North America. The rivalry between Elssler and Taglioni and their supporters was intense although they had very different styles.

Elssler was fiery, exotic and sexy, while Taglioni excelled in creating unearthly, spiritual characters. Theophile Gautier, a ballet critic and an Elssler fan, snidely described Taglioni as a Christian dancer (implying she was rather cold), while he proclaimed that Elssler was a pagan dancer (implying that she was sexy).

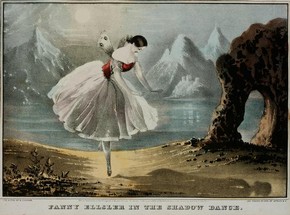

In this print Fanny Elssler is performing one of her most famous dances, the cachucha. Based on the Spanish dance, Elssler's sensual and flirtatous cachucha was the sensation of the ballet Le Diable Boiteux in 1836. It became her trademark.

Elssler was born in Austria in 1810 and with her sister appeared with the famous Viennese Children's Ballet. At 12, she joined the corps at the Hoftheater under ballet master Filippo Taglioni, and later studied briefly with the famous Auguste Vestris.

Elssler was one of the first international dance stars, and one of the first to tour America – a major undertaking in the years before the railways were established.

Print of Fanny Elssler in the Shadow Dance, N Currier, lithograph coloured by hand, New York, America, 1846. Museum no. S.2599-1986

On the voyage over she was attacked by a sailor but dealt him such a kick that he died a few days later.

The popular image of the Romantic ballerina as an otherworldly, ethereal being was portrayed in lithographs. These were popular before photography. They showed ballerinas poised on flowers, reclining on clouds and floating through the air. Many ballerinas did perform these feats on stage, but with more than a little help from stage technology.

Fanny Cerrito and Carlotta Grisi were two other stars of the Romantic ballet.

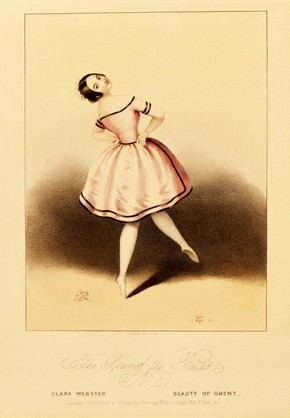

Clara Webster

Unlike other European countries, England never produced a great Romantic ballerina.

Print depicting Clara Webster in The Beauty of Ghent, L'Enfant (print), lithographic print, about 1844. Museum no. E.5065-1968

England did not have a national ballet school attached to a major opera house, although several London theatres provided dance training.

The talented Clara Webster, who London critics prophesied would be the first great English ballerina, had her career cut tragically short when her dress caught fire on stage.

In the 1840s, Clara Webster was hailed as British ballet's 'most promising star' - the first English dancer talented enough to challenge the popular prejudice that ballet belonged to the French or Italian ballerinas.

In 1844 she was dancing in The Revolt of the Harem at Drury Lane when her dress brushed the flame of an oil-burning lamp on the stage. Her flimsy ballet dress went up in flames in seconds. None of her colleagues dared go near to help and the fire buckets were all empty. Finally a stagehand threw himself on top of her and smothered the flames.

No one thought to bring down the curtain so the audience witnessed the whole event. Clara was carried backstage and an announcement made that her injuries were not too serious, so the ballet continued. She died three days later from her burns. She was just 23 years old.

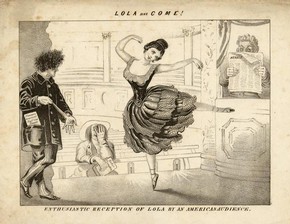

Lola Montez

Lola Montez is remembered for her outrageous and flamboyant life rather than for any significant talent as a dancer.

She was born plain Eliza Gilbert in Ireland in 1818. Trading on her dark colouring and exotic beauty, she reinvented herself as a Spaniard and, after only five months' training, launched herself in 1843 as a Spanish dancer.

All London flocked to see her debut, but during the performance one of her rejected suitors shouted 'Dammit! It's Betty James!' after which she lost credibility.

Europe, however, raved. Her admirers included famous authors, among them Dumas and Balzac, and the composer Franz Lizst. By 1847 she was mistress of King Ludwig of Bavaria and virtually controlled his government.

Louise Farebrother as Abdullah, colour lithograph, January 1848. Museum no. E.5008-1968

Banished in 1848, she resumed her stage career. In London her appearances were cancelled because she was appearing in court on a bigamy charge. In Australia she horsewhipped the editor of the Ballerat Times. In New York she lectured on the 'Care of the Bust'.

Like many others who led full and rich lives, she later repented of her colourful past and devoted her last years to helping fallen women.

No comments:

Post a Comment