When Giselle dances with Loys - Recorded, 2004

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jOVtj9CYJCA

Giselle Research

Sunday, 11 December 2011

Romantic Ballet

In the early 19th century the Age of Reason gave way to the age of the imagination and the Romantic Movement.

Young artists, writers, poets and dancers wanted the freedom to express themselves in a spontaneous and individual way. Rejecting the classical ideas of order, harmony and balance they turned to nature as a source of inspiration. As people left the countryside and agriculture for the growing urban industries and factory work, the Romantic vision was partly a plea for a return to a ‘natural’ life and partly escapism.

Although most ballets were created by men, the male dancer was no longer an equal star. In the following decades dance became an unacceptable career for a man. Male roles were often taken by women dressing en travestie. Men only appeared in character roles.

Marie Taglioni, La Sylphide, Alfred Edward Chalon (RA), Richard James Lane (A.R.A). lithograph, coloured by hand, London. Museum no. S.2610-1986

The Cult Of The Ballerina

By the 1840s women had become the great ballet stars and ballerinas wore the familiar bell shaped dress with cap sleeves, low cut bodice and long skirts. If you look at fashion plates of the period you can see that costumes developed from fashionable dress of the time. Ballerinas also learned the art of dancing on the very tips of their toes, known as pointe work. There were no stiffened pointe shoes and dancers darned the toes of their slippers to give additional support.

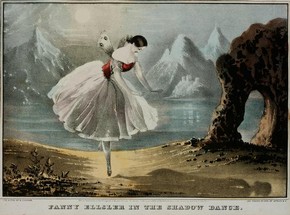

The great Romantic ballerinas were idolised throughout Europe. Marie Taglioni danced in Paris, St Petersburg, London and Italy and Fanny Elssler even toured North America. The rivalry between Elssler and Taglioni and their supporters was intense although they had very different styles.

Elssler was fiery, exotic and sexy, while Taglioni excelled in creating unearthly, spiritual characters. Theophile Gautier, a ballet critic and an Elssler fan, snidely described Taglioni as a Christian dancer (implying she was rather cold), while he proclaimed that Elssler was a pagan dancer (implying that she was sexy).

In this print Fanny Elssler is performing one of her most famous dances, the cachucha. Based on the Spanish dance, Elssler's sensual and flirtatous cachucha was the sensation of the ballet Le Diable Boiteux in 1836. It became her trademark.

Elssler was born in Austria in 1810 and with her sister appeared with the famous Viennese Children's Ballet. At 12, she joined the corps at the Hoftheater under ballet master Filippo Taglioni, and later studied briefly with the famous Auguste Vestris.

Elssler was one of the first international dance stars, and one of the first to tour America – a major undertaking in the years before the railways were established.

Print of Fanny Elssler in the Shadow Dance, N Currier, lithograph coloured by hand, New York, America, 1846. Museum no. S.2599-1986

On the voyage over she was attacked by a sailor but dealt him such a kick that he died a few days later.

The popular image of the Romantic ballerina as an otherworldly, ethereal being was portrayed in lithographs. These were popular before photography. They showed ballerinas poised on flowers, reclining on clouds and floating through the air. Many ballerinas did perform these feats on stage, but with more than a little help from stage technology.

Fanny Cerrito and Carlotta Grisi were two other stars of the Romantic ballet.

Clara Webster

Unlike other European countries, England never produced a great Romantic ballerina.

Print depicting Clara Webster in The Beauty of Ghent, L'Enfant (print), lithographic print, about 1844. Museum no. E.5065-1968

England did not have a national ballet school attached to a major opera house, although several London theatres provided dance training.

The talented Clara Webster, who London critics prophesied would be the first great English ballerina, had her career cut tragically short when her dress caught fire on stage.

In the 1840s, Clara Webster was hailed as British ballet's 'most promising star' - the first English dancer talented enough to challenge the popular prejudice that ballet belonged to the French or Italian ballerinas.

In 1844 she was dancing in The Revolt of the Harem at Drury Lane when her dress brushed the flame of an oil-burning lamp on the stage. Her flimsy ballet dress went up in flames in seconds. None of her colleagues dared go near to help and the fire buckets were all empty. Finally a stagehand threw himself on top of her and smothered the flames.

No one thought to bring down the curtain so the audience witnessed the whole event. Clara was carried backstage and an announcement made that her injuries were not too serious, so the ballet continued. She died three days later from her burns. She was just 23 years old.

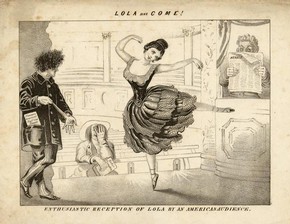

Lola Montez

Lola Montez is remembered for her outrageous and flamboyant life rather than for any significant talent as a dancer.

She was born plain Eliza Gilbert in Ireland in 1818. Trading on her dark colouring and exotic beauty, she reinvented herself as a Spaniard and, after only five months' training, launched herself in 1843 as a Spanish dancer.

All London flocked to see her debut, but during the performance one of her rejected suitors shouted 'Dammit! It's Betty James!' after which she lost credibility.

Europe, however, raved. Her admirers included famous authors, among them Dumas and Balzac, and the composer Franz Lizst. By 1847 she was mistress of King Ludwig of Bavaria and virtually controlled his government.

Louise Farebrother as Abdullah, colour lithograph, January 1848. Museum no. E.5008-1968

Banished in 1848, she resumed her stage career. In London her appearances were cancelled because she was appearing in court on a bigamy charge. In Australia she horsewhipped the editor of the Ballerat Times. In New York she lectured on the 'Care of the Bust'.

Like many others who led full and rich lives, she later repented of her colourful past and devoted her last years to helping fallen women.

Thursday, 3 November 2011

The influences of Sir Frederick Ashton

Anna Pavlova

Anna Pavlova was the illegitimate daughter of a laundry-woman. Her father was probably a young Jewish soldier and businessman. When she saw The Sleeping Beauty performed, Anna Pavlova decided to become a dancer, and entered the Imperial Ballet School at ten. She worked very hard there, and on graduation began to perform at the Maryinsky Theatre, debuting on September 19, 1899.

In 1907, Anna Pavlova began her first tour, to Moscow, and by 1910 was appearing at the Metropolitan Opera House in America. When, in 1914, she was traveling through Germany on her way to England when Germany declared war on Russia, her connection to Russia was for all intents broken.

For the rest of her life, Anna Pavlova toured the world with her own company and kept a home in London, where her exotic pets were constant company when she was there. Victor Dandré, her manager, was also her companion, and may have been her husband (she deliberately clouded this issue).

While her contemporary, Isadora Duncan, introduced revolutionary innovations to dance, Anna Pavlova remained largely committed to the classic style. She was known for her daintiness, frailness, lightness and both wittiness and pathos.

Her last world tour was in 1928-29 and her last performance in England in 1930. Anna Pavlova appeared in a few silent films: one, The Immortal Swan, she shot in 1924 but it was not shown until after her death -- it originally toured theaters in 1935-1936 in special showings, then was released more generally in 1956.

Anna Pavlova died of pleurisy in the Netherlands in 1931.

http://womenshistory.about.com/od/dance/p/anna_pavlova.htm

The world will forever remember the Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova, who brought a more traditional feel to classical ballet.

Anna Pavlova died of pleurisy in the Netherlands in 1931.

http://womenshistory.about.com/od/dance/p/anna_pavlova.htm

The world will forever remember the Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova, who brought a more traditional feel to classical ballet.

On her ninth birthday, Anna's mother treated her to a performance of The Sleeping Beauty, a ballet that forever changed Anna's life. She decided then that she would one day dance on stage. She began taking ballet lessons and was quickly accepted into the Imperial Ballet School.

Anna was not a typical ballerina of her day. At only five-feet-tall, she was delicate and slender, unlike most of the students in her classes. She was exceptionally strong and had perfect balance. Anna possessed many unique talents. She soon became a prima ballerina.

Anna formed her own ballet company and went on tour, introducing her classical style of ballet to the world. She visited several countries, traveling over 500,000 miles by boat and train. She gave over 4,000 performances.

Anna was known to have had very arched feet, which made it hard to dance on the tips of her toes. She discovered that by adding a piece of hard leather to the soles, the shoes provided better support. Many people thought of this as cheating, as a ballerina should be able to hold her own weight on her toes. However, her idea was the precursor to the modern pointe shoe.

Anna Pavlova believed that dancing was her gift to the world. She felt that God had given her the gift of dance to delight others. She often said that she was "haunted by the need to dance." She became an inspiration to young boys and girls to learn how to dance and experience the joys of ballet.

http://dance.about.com/od/famousdancers/p/Anna_Pavlova.htm

http://dance.about.com/od/famousdancers/p/Anna_Pavlova.htm

Sir Frderick Ashton

Although we think of Frederick Ashton as the most English of choreographers, he was actually born in Ecuador, on September 17th 1904, and then spent his early years in Peru, where his father was a diplomat. It was while he was at school in Lima that he first saw Anna Pavlova, an event which changed his life: he became determined to be a dancer - and not just any dancer, but 'the greatest dancer in the world' - and his love for Pavlova remained a major influence on his choreography throughout his whole career.

Ashton came to England when he was 15, as a boarder at Dover College, and left school after three unhappy years only to move into a dreary job which he hated. He started ballet lessons with Leonide Massine on Saturday afternoons, and eventually persuaded his family that he should train full-time. When Massine moved away from London he sent Ashton to Marie Rambert - one of those seemingly unimportant decisions which changes history, for it was Rambert's clever eye which saw the potential choroegrapher in the would-be dancer, and entrusted him with his first ballet, A Tragedy of Fashion

Ashton left Rambert for a year to dance with Bronislava Nijinska, another of the the major influences on his work, and when he returned he began choreographing regularly for Rambert, making works for her Ballet Club, to be performed on the handkerchief-sized stage of the Mercury Theatre. At the same time he started making work for Ninette de Valois and the Vic-Wells ballet, and in 1935 he left Rambert and joined de Valois permanently. (Poor Rambert, fated so often to develop a wonderful talent and watch it walk away.) His first major work for the Vic-Wells was the 1933 Les Rendezvous, made for Alicia Markova; when Markova left the company he focused his attention on her successor, a young girl called Margot Fonteyn

Ashton's career was interrupted by war service, but he returned in triumph when the company moved to Covent Garden in 1946, making one of his greatest ballets, Symphonic Variations, to show that he could master the space of a huge stage. When de Valois retired in 1963 he became Director of the Royal Ballet, introducing to the repertoire some great works from outside - Nijinska's Les Noces, Balanchine's Serenade - as well as unwittingly defining the course the company was to take in the future by asking Kenneth MacMillan to make a new version of Romeo and Juliet. His directorship ended in 1970, in circumstances still argued about but which caused him deep hurt which he never quite forgave.

He continued to make ballets for the company until a few years before his death: the last major work was Rhapsody, made for Baryshnikov in 1980. He died at his Suffolk home on August 19th, 1988.

Although we think of Frederick Ashton as the most English of choreographers, he was actually born in Ecuador, on September 17th 1904, and then spent his early years in Peru, where his father was a diplomat. It was while he was at school in Lima that he first saw Anna Pavlova, an event which changed his life: he became determined to be a dancer - and not just any dancer, but 'the greatest dancer in the world' - and his love for Pavlova remained a major influence on his choreography throughout his whole career.   Ashton (far right) rehearsing at the Ballet Club Photograph by courtesy of the Royal Opera House |

Ashton made more than eighty ballets, far too many of which have been lost over the years. His biographer David Vaughan keeps an updated chronology which gives details of each one, with a list of different productions. We have reviews of most of the surviving works in our database, and a growing number of special pages about individual ballets, and we list those here. More will be added as the season progresses.

Court Ballet

Ballet evolved from social court dances in Italy and France. Wealthy people, including royalty, would try to outdo each other by having the most elaborate courts. Court dances were derived from various steps and rhythms of folk dances, but they were much more elaborate. They often featured elaborate scenery and beautiful costumes, plus a series of processions, poetry reading, music, and of course, dancing. These social dances soon evolved into a choreographic form, the ballet de cour.

Eventually, court dances moved to the stage, bringing a change in choreography, as the dancers were then seen from only one direction instead of three. Turnout began to gain more and more importance. Costumes were elaborate, though very restrictive. Port de bras evolved in order to show off the beauty of the costumes - dancers found that a slight turn of the body could spotlight certain details of their costumes.

http://dance.about.com/od/historyofdance/f/Court_Ballet.htm

Eventually, court dances moved to the stage, bringing a change in choreography, as the dancers were then seen from only one direction instead of three. Turnout began to gain more and more importance. Costumes were elaborate, though very restrictive. Port de bras evolved in order to show off the beauty of the costumes - dancers found that a slight turn of the body could spotlight certain details of their costumes.

http://dance.about.com/od/historyofdance/f/Court_Ballet.htm

Wednesday, 2 November 2011

The Architects Of Classical Ballet

‘Classical ballet’ as a technique derives from a set of codified principles – the placement of the feet, the iconic steps and stances, the clarity and proportion of the positions originally devised in the highly elaborate social world of the French courts. Petipa developed this style to virtuoso levels, displaying the brilliance of his dancers as if to raise a mirror to the grandeur of his Russian imperial audience. The ballerinas’ short, stiffened tutus showed off their fancy footwork and perfect alignment. Their ‘steely’ pointe work, sharper and harder than the softer romantic style, emphasised precision, line and balance.

But classical ballet is not just technique, it is also theatre. In this respect, too, Petipa both played to his aristocratic imperial audience and led them to new heights. His first major success was The Pharaoh’s Daughter (1862), an elaborate, evening-length epic with a cast of 400 dancers that established the fashion for the ballet à grand spectacle.

In these sprawling productions, classical ballet dancing was reserved for the principal roles, and interspersed with ‘character’ or ‘national’ dances. These balleticized imaginings of folk or regional dances were used to add splashes of local colour or to create alluring mirages of far-off places. Highly stylized mime sequences were used to spell out particular moments in the story, and to offer a vital change of pace between set pieces.

The opulence of these dance extravaganzas made Petipa successful, but they are not what made him great. That was down to the skill of his choreography, both for thecorps de ballet and for the soloists.

http://www.roh.org.uk/discover/ballet/choreographers/petipa/context.aspx

Marius Petipa

Marius Petipa was born in Marseilles March 11, 1822. His father Jean Antoine Petipa was a dancer, choreographer and teacher who brought up both Marius and his elder brother, Lucien, to follow the same profession. Lucien made a better name for himself as a dancer; among the many roles he created was that of Albert (Albrecht) in Giselle.

Marius Petipa began his dance studies at age 7, but at first did not care much for the art form. He received a general education from the Grand College in Brussels. His performing debut came as a child in his father’s production of Pierre Gardel’s La Dansomanie in 1831 at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels. The Belgian revolution followed soon afterwards placing the family in dire straits. Jean Petipa moved the family to Bordeaux in 1834, and then on to Nantes where Marius became a principal dancer in 1838.

Marius and his father Jean toured North America in 1839 after which Marius studied with Auguste Vestris in Bordeaux. There he appeared as principal dancer in many ballets including, Giselle, La Fille mal Gardée and La Péri. A noted partner, Marius’ partnering of Carlotta Grisi in La Péri was spoken of for generations, particularly one partnered catch that Gautier deemed would become "... as famous as the Niagara Falls."

In Bordeaux Marius Petipa also choreographed his own work, La jolie Bordelaise, La Vendange, L’Intrigue amoureuse and Le Langage des fleurs. Following the failure of the impresario in Bordeaux Marius was immediately engaged at the King’s Theatre, Madrid. He remained in Spain as a dancer for four years, also studying Spanish dance. This influence led him to choreograph Carmen et son Toréro, La Perle de Séville, L’Aventure d’une fille de Madrid, La Fleur de Grenade, and Départ pour la course des taureaux.

In 1846 he began a love affair with the wife of the Marquis de Chateaubriand, a prominent member of the French Embassy. Learning of the affair the Marquis challenged Petipa to a duel. Petipa quickly left Spain, never to return. On May 24, 1847 he went to St. Petersburg at the suggestion of ballet master Titus. He was offered a contract for one year as a principal dancer, replacing another Frenchman (Emile Gredlu) who was leaving.

Petipa was alarmed to discover that the company had just begun a four-month holiday, but his concern turned to delight on learning that he would receive full pay for the period. For his debut he assisted dancer Frédéric in mounting Joseph Mazillier’s Paquita on the imperial stage, and he enjoyed much success in the largely mimed role of Lucien d’Hervilly. By February 1848, Petipa and his father had produced Mazilier’s Le Diable amoureux. Since Marie Taglioni’s departure from St. Petersburg in 1842 the ballet had slumped into insignificance. At the end of Petipa’s first season in Russia the critic Raphael Zotov wrote, "Our lovely ballet company was reborn with the production of Paquita, and the production of Satanilla [as Le Diable amoureux came to be known in Russia] and its superlative performance placed the company again at its former level of glory and universal affection." The first ballet he choreographed in Russia was The Swiss Milkmaid (1849).

The ability to mount revivals and make dances was the predictable outcome of Petipa’s rigorous apprenticeship, evidenced by his composing ballets as a teenager in Nantes and later in Bordeaux and Spain. The next step - allowing skill to ripen into creativity - took many years.

Petipa’s superiors could not have sensed the depth of his flair for ballet production (given his lack of celebrity at the time, it likely would have made no difference) when Jules Perrot was called to St. Petersburg in 1848 at the behest of Fanny Elssler to become resident ballet master. The immediate effect of Perrot, a choreographer of international stature, on Petipa’s career was to reaffirm his duties as a dancer. Despite some minor works (his first work in St. Petersburg was The Star of Granada in 1855) Petipa’s muse fell silent for a decade. From performing the ballets of Perrot and Arthur Saint-Léon, Petipa did learn the value of intensely dramatic mimed scenes and the persuasive intervention of fantastic elements into everyday settings. He was also chosen by Perot to assist him in producing new ballets.

This assimilated knowledge enriched Petipa’s native talents as a superior mime, an expert character dancer, and behind the scenes, a politically astute courtier observing the state of ballet affairs. By the late 1850s Petipa must have known Perrot’s days in St. Petersburg were numbered. He returned modestly to choreography with A Regency Marriage (1858), The Parisian Market (1859) and The Blue Dahlia (1860) all of which were vehicles for Maria Sergeyevna Surovshchikova, whom Petipa had married in 1854. They had three children, one of whom became a well-known dancer, Marie Mariusovna.

For Petipa, who turned 40 in 1858, composition was a logical alternative to dancing. Petipa’s breakthrough as a choreographer came in 1862 with the creation of La Fille du Pharaon based on a novel by Gautier. On the strength of the success of this ballet Petipa was appointed one of the company’s ballet masters. He was successful in unseating Saint-Léon, who had replaced Perrot, by championing Surovshchikova in a public rivalry against Marfa Muravieva whom Saint-Léon favored. Petipa was promoted to take charge of the Maryinsky company in 1869, the year that also saw the premiere of his Don Quixote.

Petipa established himself with his "ballets à grand spectacle", of which Le Roi Candaules (1868) and La Bayadère (1877) count. Hardly a new idea - ballets set in exotic locales had been around since the French Baroque - but Petipa linked the ballets to current events or fashions. La Bayadère came in the wake of a widely reported journey of the Prince of Wales to India.

Petipa’s "ballet à grand spectacle" called for massive forces, luxurious productions and predictable choreographic components. In constructing the acts of a ballet he selected from a variety of elements: massed scenes, character dances which provided a sense of local color, classical dances (which normally called for a suspension of the narrative) and dramatic encounters between the principal characters, set either as pure mime or in "pas d’action", a mixture of mime and dancing.

Petipa was meticulous in his preparations, doing exhaustive research and preparing minute plans for painters and composers. He always considered, however, that choreography should take precedence over all else. He would come to rehearsals with ideas already prepared and teach the dancers what he had devised. "Without even looking at us he merely showed us the movements and gestures with words spoken in indescribable Russian," wrote Kschessinka. Despite his many years in Russia, Petipa spoke little of the language and the dancers had to get used to his peculiar idioms. "You on me, me on you; you on mine, me on your," meant that you had to move from one corner ("you") to where he was ("me"). To make his meaning clearer he tapped his chest every time he said "me." By this means Petipa taught some of the most widely performed and enduring masterpieces ballet has yet known.

Petipa married a second time in 1882 to a member of the Moscow Ballet, Lubova Leonidovna.

Inevitably with such a long career (56 years in the service of the one company), fashion turned against Petipa. Although officially titled ‘ballet master for life’, the disaster of his The Magic Mirror (1903) brought about a retirement order. He retired with full ballet master’s pay. In 1906 Petipa’s memoirs were published, then subjected to harsh attack. Due to ill health Petipa moved to Gurzuf in southern Russia in 1907 where he lived until dying on July 14, 1910.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)